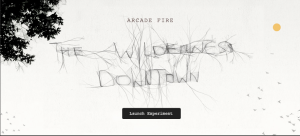

Chris Milk’s interactive online film The Wilderness Downtown mixes music video + documentary + personal history + Google satellite images + browser art. Try it out! The project is a collaboration with the band Arcade Fire, and is labeled “an experiment”.

Earlier Chris Milk worked on The Johnny Cash Project, a crowd-sourced video set to Cash’s “Ain’t No Grave.”

I’ve recently published a paper with cartographer Sebastien Caquard in the Art & Cartography special issue of The Cartographic Journal. Here’s a description:

Mapping Globalization: A Conversation between a Filmmaker and a Cartographer

This paper is an edited version of a written dialogue that took place between the fall of 2008 and the summer of 2009 between a filmmaker (Amelia Bryne) and a cartographer (Sebastien Caquard) around the issue of representing globalization. In these conversations, we define some of the key means for representing globalization in both mapmaking and filmmaking discussing local/global, strategic/tactical, data/narrative and unique/multiple perspectives. We conclude by emphasizing the potential impact of new media in ushering in hybrid digital products that merge means of representation traditional to filmmaking and cartography.

It begins …

SC. Why would a filmmaker like you involved in exploring globalization through film be interested in maps and cartography?

AB. In my view cartography and cinema have a similar problem at heart: how can we represent the world in a meaningful and engaging way? These representations can be made with many kinds of information – fragments of the world – including information in the form of scientific data, or about spatial and temporal relationships, cultural practices, and even individual perceptions or emotions. These two disciplines seemingly address the challenge of constructing representations of the world from different angles, and I am interested in exploring them. More specifically, I am interested in exploring how the combination of these two practices could be complementary in terms of understanding and representing globalization, which is a significant focus of the work of many contemporary filmmakers, including myself.

SC. So, you are interested in cartography as a domain that could help you to better represent globalization in your films. Could you elaborate a bit?

AB. My desire to represent globalization is perhaps my way of saying that I want to find ways of making sense of what is happening in the world today, and I think that cartography might be able to help me do that. Globalization is a name for a collection of phenomena that characterize and influence contemporary politics, business and everyday life. Globalization operates at multiple scales, from the personal to the global, and impacts both humans and our environment. It spans issues ranging from the influence of transnational organisations, to global labour and global capital movements, to deregulation and privatisation, oil, scarce resources, intellectual property rights, China, containerized shipping, export processing zones, and anti-globalization movements (Zaniello, 2007, p. 2). Globalization and its associated flows of capital, people, and objects is challenging to make sense of. It challenges traditional forms of representation and resistance (Jameson, 1991).

Film theorist Holly Willis suggests an explicit connection between films and maps in the context of globalization. She frames films as a type of ‘map’ that may be able to capture the increasing complexity of the world in a different way than more literal cartographic representations. This desire for alternative or hybrid forms of mapping stems from a dilemma of representation: ‘How do you ‘‘map’’ a global economy, a vast military industrial complex, or the convergence of gigantic corporations? How do you chart multinational banking and stock exchanges, or the increasingly powerful web of bureaucratic control?’ (Willis, 2005, pp. 74–75). Those are the questions I hope cartography could help me to address. Maybe, as Willis suggests, filmmaking and cartography could be helpful to each other.

Etc …

Filed under: Interface, Production Models | Tags: activism, Documentary, participatory

My first contact with documentary-as-a-tool-for-change was at a Washington, DC anti-globalization protest in the spring of 2000, where I hung out with an Indymedia crew (and, as a documentary student admired their camera). The event was not much covered by mainstream TV – except by a few rather frightened looking local newscasters in suits – but there were lots of cameras operated by small video crews and various photographers.

I think that a lot of documentary media makers make media that we hope will change things – to bring a problem to light, to help people see an issue in a different way, etc. It’s always been tricky for me to reconcile what the relationship actually is between media and social change – have I ever seen a film that has truly changed the way I look at things? I think that much more than watching films themselves, it is the process of making media – talking to storage unit owners, wrangling through an idea, visiting abandoned factories – that has changed me.

I have been thinking lately that some methods of media making put process first, while others prioritize product, and that this is a very important distinction. For example, participatory video (see this book), power mapping, and issue mapping put process first – the point of these activities is to participate in the process itself. These methods can be used as co-inquiry tools, and may help to surface people’s ideas of what the issues at hand are and how to solve them. They also may surface people’s assumptions and theories of change. The final product of such exercises in raw form (post-it notes on a wall, DIY videos, etc.) may not be particularly meaningful to those outside the group that produced them, though they could be translated into documents designed for an outside audience.

Alternatively, documentary films and research-based articles typically put product first. The audience is expected to learn by consuming the product instead of learning by participating in its creation (the creation process is left to the “expert”). Recently, a number of documentary films have attempted to bridge this gap by providing study or discussion guides to accompany the film. For example, Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. Though this may help audiences to engage more deeply with the issues presented, this strategy is probably not a substitution for participation in the making-process itself.

I spoke recently with Montreal-based cartographer Sébastien Caquard whose work focuses on the intersection between cinema and cartography. I’ve been interested in the meeting between films and maps as well in the context of thinking about how cinema might deal with ‘data’.

“The encounter between two disciplines doesn’t take place when one begins to reflect on another, but when one discipline realizes that it has to resolve for itself and by its own means, a problem similar to that confronted by the other [for example, the “problem” of narrative, or the “problem” of how to represent reality].” – Gilles Deleuze

Filmmakers and cartographers deal with a similar question: How can we represent information in a meaningful and engaging way? While filmmakers and mapmakers have traditionally created distinctly different visual products, films and maps have long been caught in an intriguing crossover. It is possible to find cinematic elements and strategies in maps, as well as cartographic elements and strategies in cinema. See the books Cartographic Cinema, The Atlas of Emotion, and The Sovereign Map.

For example, films set in particular cities might be read as guided ‘maps’ of those cities at different moments in history, and from various points of view. The film spring wind will bring life again can be seen as a kind of ‘map’ of contemporary Beijing. The first part of the film focuses on the world at large and the economic and political relationship between the U.S. and China, the second reveals the city itself – focusing on everyday categories like traffic, crowds, restaurants, grocery stores, bars, tv, etc.. The final section tells the story of a woman who, like hundreds of thousands of others, was displaced from the center of the city (to a new suburb) when her home was torn down in the effort by the government to modernize Beijing and present it for the 2008 Olympics. In essence, the film proceeds as a zoom from the global, to the city, to the individual.

Both maps and films are increasingly made and presented digitally, creating new possibilities for overlap between the two, yet there has been little explicit exploration of how the two forms may begin to merge more significantly. For instance, digital technology has the potential to help maps become more cinematic through multimedia (sound, video, photo, etc.), narrative, and emotion. Some hybrid map/multimedia forms are being explored – documented in the excellent book Else/Where Mapping – but, for the most part, these practices remain on the fringes of cartography.

Sébastien and I are planning to write a paper together for a special issue on Art and Cartography of the Cartographic Journal, investigating, in part, whether there are digital products that can be read as both ‘maps’ and ‘films’, and what these might look like.

Question:

Could these film-map hybrids better or newly represent global/corporate/collaborative/data-filled life today?

“In his book The Image of the City, writer Kevin Lynch shows how the ability to map, from memory, the spaces in which we live corresponds directly to our feelings of either belonging or alienation, and by extension, our sense of political engagement and empowerment. But the ability to map our world has grown increasingly complex with the rise of tremendously powerful transnational corporations, unbridled competition and the unrestrained pursuit of self-interest. How do you ‘map’ a global economy, a vast military industrial complex, or the convergence of gigantic corporations? How do you chart multinational banking and stock exchanges, or the increasingly powerful web of bureaucratic control?” (New Digital Cinema, p. 74-75).

I like this short exchange between Doug Aitken and Matthew Barney, two creators of massive-scale cinematic art projects.

Doug Aitken:

The weight of film production is a heavy one. We’re coming into a new era of lightness and nomadism, where a sixteen-year-old with a Mac can direct, shoot, and cut a film. I’m interested in seeing how this changes the Hollywood studio system.

Matthew Barney:

Hollywood blockbuster films are so over the top, they have become something else entirely. Like you, I am interested in either end of the spectrum. It is everything in the middle – the straight-on storytelling stuff – that I am not really interested in, like so-called independent film.

From: Broken Screen: Expanding the Image, Breaking the Narrative, 26 Conversations, p. 72, 2005.

I like the sense that this exchange paints of the film world – at one end of the spectrum there is the luxurious ideal of having all the resources you need to realize a visually luscious project: rich colors, on location in Tahiti, a constant supply of Alessi coffee/cups for the crew.

But, at the other end there is something beautiful too: the beauty of movement, simplicity, nomadism: where you use the medium to document what you see around you in a way that is closely connected to your own body and way of seeing.

This nomadism is similar to the concept of a video or film “camera as pen”, the idea that the camera is a powerful individual tool for observation and presentation, and that filmmaking does not need a trunk-full of lights and electrical cables & stacks of location releases to be powerful. (e.g. Why bother with everything in the middle?!)